An Opinion by Andi Cockroft

We cannot say we were never warned.

It is now at the stage where the very mention of the term “Expert” immediately raises mistrust in my mind’s eye. And seeing so many (especially the young) saying “Trust the Experts” makes me fearful for the future.

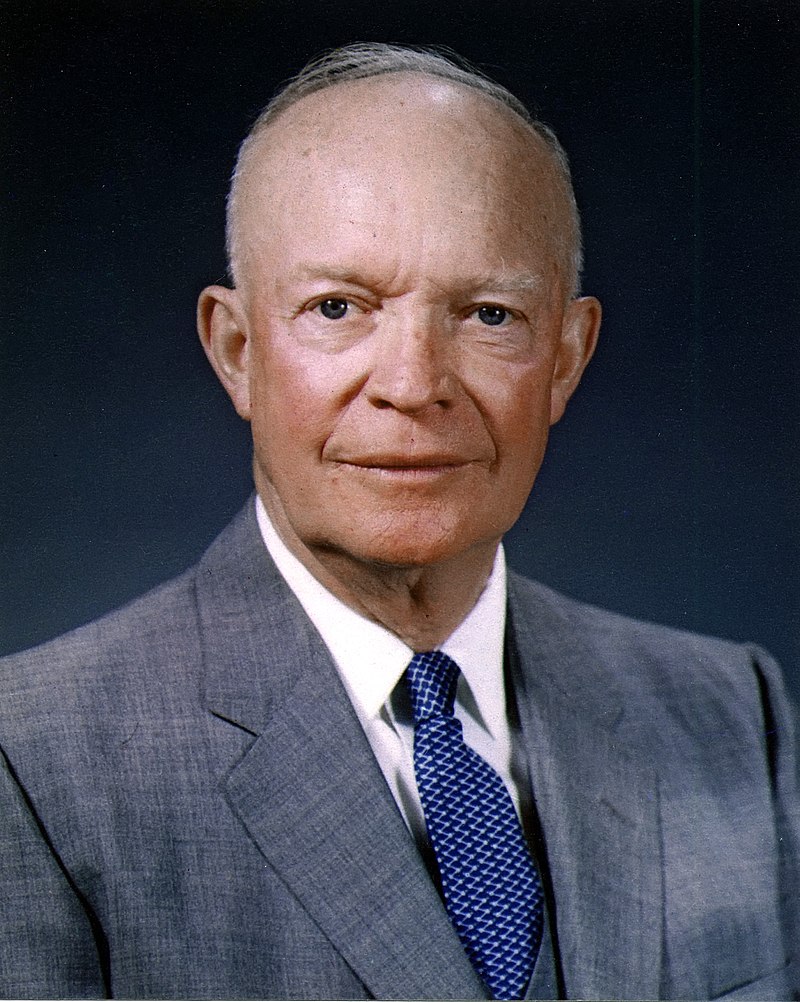

In his farewell address to the US way back in January 1961, Eisenhower famously predicted the capture of science and the scientific method:

“Akin to, and largely responsible for the sweeping changes in our industrial-military posture, has been the technological revolution during recent decades.

In this revolution, research has become central, it also becomes more formalized, complex, and costly. A steadily increasing share is conducted for, by, or at the direction of, the Federal government.

The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocation, and the power of money is ever present and is gravely to be regarded.

Yet in holding scientific discovery in respect, as we should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite”

Perhaps the earliest I recollect, is when Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring came out in 1962.

Many Americans were horrified to learn about the dangers to humans and other life posed by pesticides. Critics quickly pushed back, and, as environmental historian Maril Hazlett writes, they did so in tremendously gendered terms, depicting Carson and the women who were moved by her messages as over-emotional and irrational.

Carson, a biologist by training, made the case against the pest-control methods used at the time. Her book presented the relationship between humans and nature in a ground-breaking way. Hazlett notes that many readers cited a passage describing how the same man-made chemicals were found in “fish in remote mountain lakes, in earthworms burrowing in soil… in the mother’s milk, and probably in the tissues of the unborn child.” Given such immense complexity, Carson pointed out that contemporary scientific knowledge was far too limited to justify enormous chemical interventions in the natural world.

Some scientists embraced Carson’s notion that the public must be included in evaluations of ecological dangers, which had previously been limited to industrial and agricultural representatives and government officials.

But other scientists, along with industry representatives, government personnel, and segments of the media, pushed back with a vengeance. A review in Time accused Carson of being “hysterically overemphatic” with a “mystical attachment to the balance of nature.” A cover illustration for the industry magazine Farm Chemicals depicted a witch on a broomstick, clearly referring to Carson. Dr Robert Metcalf, vice-chancellor of the University of California at Riverside, asked whether “we are going to progress logically and scientifically upward, or whether we are going to drift back to the dark ages where witchcraft and witches reign.”

But what of little old GodZone?

There are many examples hidden away in New Zealand’s archives. One case concerned an American biologist Thane Riney who came to New Zealand in the mid-1950s to work for the Department of Internal Affairs.

In 1930 a government conference titled “The Deer Menace” declared wild deer to be a menace in New Zealand. The outcome was not unexpected for the title strongly suggested what the outcome would be. Perhaps then Riney was intrigued by the anti-deer policy of New Zealand for in the USA deer were managed as a desirable game species.

Whatever the motivation in coming “down under”, Thane Riney stepped into the New Zealand scene joining the Internal Affairs department. He came with an open, scientific mind untainted by the assumptions of that 1930 Deer Menace Conference.

In eight years, Thane Riney produced 25 published scientific reports, a high rate jealously scorned by his bureaucratic colleagues. Riney’s research left its mark. He had examined “undisturbed” deer and possum populations at the remote Lake Monk, in a rugged wilderness called Fiordland, and found that left alone, deer and possum numbers stabilised to low levels and did not explode out of control as the departmental propaganda maintained. Then a much less complex paper showed there was little or no relationship between areas of erosion-prone country and the areas of highest deer numbers.

But there are scientists and scientists and some bureaucratically tainted scientists within the department were jealous of Thane Riney’s productive work. They set out “to get him” by calling for his sacking by the Public Service Commission. But they had no grounds. The charges fell flat.

In 1958, Thane Riney no doubt somewhat frustrated by the bureaucracy in New Zealand, resigned and went to Africa to do research where his competency was appreciated.

Some years later, in 1967, Thane Riney reflected on those years with the Department of Internal Affairs and then the New Zealand Forest Service: “Unfortunately the level of competence and understanding in silvicultural (exotic forestry) matters is in no way reflected in the dealings with, or their policy toward exotic animals. This it seems to me, is due chiefly to several botanist policy-makers who have had no experience with the growth of plants in other parts of the world where browsing and grazing animals behave exactly as in New Zealand. They do not know what animals are capable of doing and what they are incapable of doing in the way of ruining forests or how to measure the effects that animals do have. Most of their recommendations are based on what the botanists are afraid the animals might do, instead of what the animals actually have done after 50 to 70 years of acclimatisation. Several of these botanists are in high administrative positions and a policy based on the simple fear of the unknown is often offered to the public as proven fact.”

A young scientist working under Thane Riney was Graeme Caughley.

Dr Graeme Caughley’s path was to follow that of Thane Riney’s. After a similarly frustrating time with the wild animal haters/exterminators, among them departmental scientists and bureaucrats. Dr Caughley headed overseas and eventually became chief research scientist and Acting Chief CSIRO, Division of Wildlife Ecology, Canberra, Australia. Dr Graeme Caughley was the author of over 130 scientific papers, articles and books – a prodigious output. He was regarded in the scientific world as foremost and eminent ecologist.

Yet another example was the late Mike Meads, a respected invertebrate scientist, who in 1992 after studying the effects of an aerial drop of 1080 in Taranaki, predicted that continued 1080 airdrops over New Zealand forests would destroy much of the food supply of ground eating birds like the kiwi.

Mike Meads warned that because 1080 wipes out many leaf litter-consuming invertebrates and micro-organisms, the litter fails to properly decompose and builds up at an alarming rate. For example one air drop of 1080 can wipe out generations of cicada larvae and they and wetas were important in the kiwi’s diet.

DOC refused to publish the papers, perhaps because at the time the $50 million budget for aerial-1080 was about to be awarded. In order to cement their case, DoC went extreme lengths to pillory Mike Meads because he dared to find the truth, contrary to departmental policy.

DOC went to fully six peer reviews hoping to discredit the Meads’ findings. Then the bureaucrats (and compliant scientists) attempted to block him from presenting his paper to a Royal Society seminar then made this scientist redundant. Meads was perturbed about the cavalier, indiscriminate way 1080 was spread from the air. He said, “Widespread aerial distribution can only have serious long term effects on forests and forest life with enormous risk of destroying the ecosystem.”

Mike Meads was no ordinary scientist. He was regarded as an authority on some of New Zealand’s rarer invertebrates, including the threatened giant wetas, he published more than 100 papers in many New Zealand and overseas journals and delivered papers to international conferences in Australia, UK and USA.

But Mike Meads wasn’t the only scientist to warn of the adverse ecological effects of 1080.

In 1989, DSIR scientist Peter Notman found many insects, particularly subsoil leaf litter feeders, were highly susceptible to the systemic and contact poisoning effects of 1080.

In 1958, Dr William Graf, a Californian Professor of Zoology, arrived in New Zealand to study the wild deer situation as Hawaii was considering introducing deer for sport. Conflicting information about New Zealand “pest” deer herds prompted the Hawaiian Board of Agriculture to send the scientist to study the situation first-hand.

William Graf viewed the New Zealand scene often in the company of departmental officers. In his report following the visit, Dr Graf wrote that there existed in New Zealand an “anti-exotic animal phobia, to an extent that much of the public as well as many government officials do not and cannot view the situation from an objective perspective.” The bureaucracies were incensed and attacked Dr Graf – again a case of harassing or bullying anyone who dares to challenge official policy.

How many so-called “Experts” can now claim their results are completely independent of their funding sources? Few if any I suggest.

Now faced with this Covid-19 crisis, there is simply an information overload of “Experts” offering all manner of solutions. Finding someone to trust seems next to impossible, so all we can do is work on the worst-case scenario and pick up the pieces of society as and when we can.