A CAUTIONARY LOOK AT NEW ZEALAND’S NEW DEVELOPMENT REGIME

Opinion by Andi Cockroft, Chair, CORANZ

Introduction: A New Era of Acceleration

The Government’s Fast-track Approvals Act has been sold to the public as a long-overdue tool to “cut through red and green tape,” turbo-charge employment, attract investment, and unlock stalled regional projects. For many New Zealanders weary of drawn-out consenting battles and bureaucratic delays, the idea has an immediate appeal. The promise is simple: faster decisions, clearer pathways, and economic stimulus in communities that need it.

But beneath the political messaging lies a very different reality. Fast-tracking, as currently designed, represents one of the most significant restructurings of environmental and resource management law in decades. It is more than a time-saver; it is a power-shift — one that alters who gets to decide what happens on our land, in our waterways, and across our conservation estate.

For outdoorspeople, hunters, anglers, trampers, rural residents, and conservation‑minded New Zealanders, the question is not whether development should occur — most accept that responsible development is necessary. The question is whether the process we use to approve such development is balanced, transparent, and protective of the natural heritage that defines this country.

The new law, as written, invites caution. Not because development is inherently damaging, but because the framework now in place tilts heavily toward expediency over scrutiny, and ministerial discretion over independent judgment. The consequences of that shift will determine the fate of landscapes and ecosystems that cannot easily be restored once damaged.

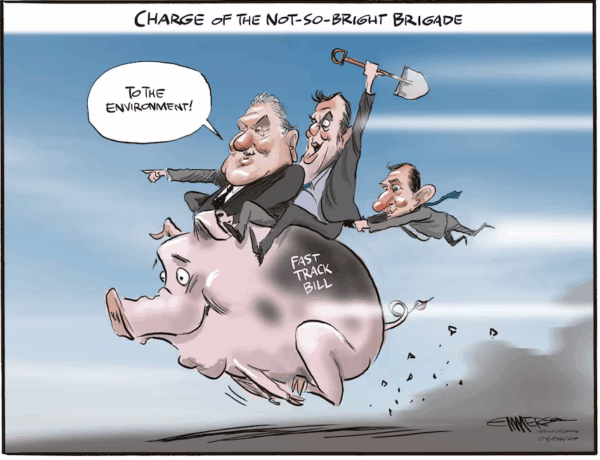

Herald cartoonist Rod Emmerson’s take on the bill

1. The Core Problem: A System Designed to Say “Yes” Quickly, and “No” With Difficulty

No one disputes that the old Resource Management Act (RMA) was slow, unevenly applied, and often needlessly adversarial. Many reasonable projects languished under layers of process. The Government’s desire to streamline decision‑making is understandable.

But the Fast‑track law does far more than shorten timeframes.

It centralises decision‑making in a small group of ministers and appointed panels, while simultaneously removing or weakening the checks that traditionally guarded against harmful outcomes.

Key characteristics include:

• Reduced public input.

• Limited independent oversight.

• Ability to override other environmental laws.

• One‑way speed favouring approval.

2. Threats to the Outdoor Environment and Conservation Estate

A. Mining and Large‑Scale Extraction on Conservation Land

Once a project is accepted into the fast‑track pathway, the conservation status of land can effectively be overridden. Rare or sensitive ecosystems may be opened to development previously considered incompatible with their protected status.

B. Loss of Meaningful Environmental Assessment

Fast‑track compresses environmental assessment into shorter timeframes, increasing the risk of incomplete or poorly scrutinised technical information.

C. Diminished Public Accountability

Public submissions are sharply curtailed, reducing the ability of hunters, anglers, and community groups to be heard.

D. Precedent Effects

A single high‑impact project approved under fast‑track encourages others, creating cumulative, long‑term environmental degradation.

3. Economic Development Need Not Be the Enemy — But It Must Be Balanced

Responsible development follows transparent processes and minimises irreversible harm. Fast‑track, as structured, elevates speed over responsibility.

4. What Must Be Changed for Fast‑Track to Be Acceptable

A. Non‑Negotiable Environmental Bottom Lines

National parks, wetlands, rare ecosystems, rivers, and key recreational corridors should be excluded from override.

B. Independent Environmental Safeguarding Body

A strong independent check is needed to review assessments and decline risky projects.

C. Guaranteed Public Input

Communities must have the right to comment on proposals affecting public land, water, or access.

D. Transparent Decision‑Making

Ministers must publicly justify approvals, impacts, trade‑offs, and rejected alternatives.

E. No Revival of Previously Declined Projects

Fast‑track must not resurrect zombie projects that failed under normal scrutiny.

F. Strict Monitoring and Enforcement

Approved projects must face real compliance oversight.

G. Protecting Public Access Rights

Development should not encroach on public rights to rivers, tracks, forests, and hunting areas.

5. The Stakes: Why Caution Matters Now

New Zealand’s remaining intact wild places exist in shrinking fragments. Once damaged, they are rarely restored.

Fast‑track shifts the burden of proof. Under the old system, developers had to show effects were acceptable. Now, much of that protection is gone.

6. A Better Path Forward

New Zealand can have both development and stewardship. But this requires balance, independence, public involvement, and respect for shared natural heritage.

Conclusion: Fast, But Not Loose

Speed has value, but only when paired with safeguards. Fast‑track, as presently structured, leans too far toward expediency at the expense of environmental protection.

CORANZ, and others who value the outdoors, have a crucial role in ensuring that “faster” does not silence “wiser.”