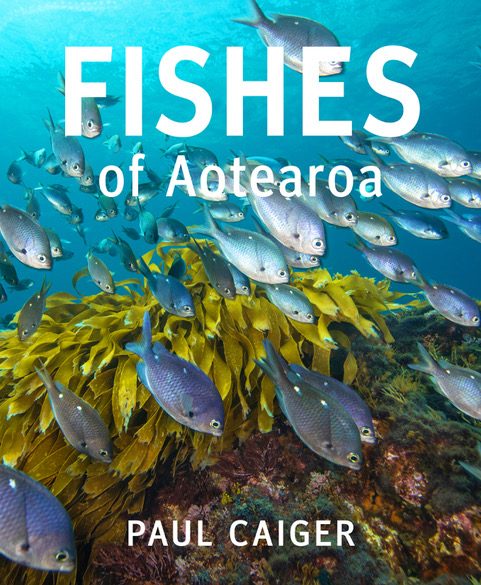

Book Review

“Fishes of Aotearoa” by Paul Caiger, published by Potton and Burton, Price $79.99. Reviewed by Tony Orman

Being insular in location, totally surrounded by sea, New Zealand with its minor islands has an aquatic ecology both in saltwater and freshwater. Author Paul Caiger, a keen scuba diver has a degree in marine biology topped by a PhD about the evolutionary ecology of New Zealand triple fin fishes. Post doctoral positions in the US researching fish acoustics and deep-sea fish biology add to his deep knowledge and eminent qualifications to write about fishes. Blend in a passion for photography to the knowledge and writing skills and there’s everything you need for a book on this subject.

There’s one last ingredient – a top publisher – and Potton and Burton with their reputation for high quality book productions, fit the bill exactly.

The author has long been captivated by Nature and in particular fishes.

He covers freshwater both native and introduced species such as trout and is not averse to exposing mismanagement. For instance the trout, both brown and rainbow, is often maligned as being an invasive predator. Yet trout have been here for 150 or so years and ecosystems adapt and food chains and predators-prey relationships eventually and usually mesh into equilibrium.

“Our iconic long fin eels (tuna) have the same conservation status as the great spotted kiwi, yet we still export the eels to other countries that have driven their own (eels) to extinction. Absurdly these native eels were recently found to be an ingredient in cat food.” In other words Man’s monetary greed and commercial exploitation is a very much far greater threat than trout and then there’s habitat with irrigation demands for corporate dairying sapping river and stream flows. Add excessive nitrates going into rivers, (toxic to fish life) and it’s obvious the biggest threat to native fish comes from human exploitation either directly of the fish species and indirectly on habitat, i.e. rivers’ flows and quality.

Yet strangely in the chapter on galaxiids, while there is brief reference to the “influential environmental factor: humans” relative to the decline of freshwater habitats, there appears no mention of commercial exploitation, which the Department of Conservation “managing” the whitebait fishery, tends to ignore the adverse impact of with no controls on commercial fishing or clamping down on bogus recreational fishers selling their catch for monetary return.

But I digress.

Ecologist’s Eyes

Overall “Fishes of Aotearoa” is a fascinating insight into the fish particularly saltwater, through the eyes of a marine ecologist. The author skilfully delves into the secret lives of fish, telling of reproduction and sexual dimporhism, camouflage techniques, schooling behaviour and other characteristics.

With his ecologist’s eye, Paul Caiger, explains the importance of interrelationships between two and even three for more species. For example snapper – in Maori language termed tamure.

“Tamure are more than just a major fishing target: due to both their abundance and ecology, they play a significant role in the reef’s ecosystems of New Zealand.”

Part of the snapper’s diet is kina – spiky sea urchins. Kina are kelp eaters. Snapper along with large koura/crayfish are the only animals on the reef that readily eat kina and in areas where snapper and crayfish are heavily over-fished, the balance between predator and prey is skewed and kina graze unchecked. The consequence is the disappearance of the kelp forest.”

“The repercussions of this are far-reaching. This is termed a trophic cascade,” writes the author.

The same consequence also involving snapper – I have been told – was around the severe decline in toheroa along the lower North Island’s west coast beaches where overfishing of snapper resulted in a population explosion of paddle crabs which decimated the shellfish.

It would have been worthwhile to have an insight, in the chapter on pelagic fish of the multi-importance of schooling feeding fish such as kahawai which benefits kingfish preying on kahawai, snapper and other fish below opportunistically grabbing sinking scraps and sea birds wheeling and feeding on surface scraps among the melee of feeding fish.

It seems the Ministry of Fisheries lacks lateral vision to understand these complexities and inter-relationships.

Perhaps in a reprinting that this fine book might deserve down the track, these food chain relationships could be added?

Paul Craiger’s explanations of the lives of fishes enhanced by his often stunning photographs and Potton and Burton’s high quality production, make for a very impressive book that any anyone with an interest in Nature and more especially anglers and divers, will find engaging and educational.

Looks a great book. On the subject of trout being seen as “invasive predators”, trout are preyed ion by native eels and native shags. So it balances out, does it not?

Looks like an interesting read.

A general lack of understanding of the complex interconnections within our various NZ river types has led to flawed models such as RHYHABSIM being used at water allocation hearings in lieu of more informative but more costly river specific studies.

This is exacerbated by such dodgy standard references as Ian Jowett’s “100 rivers study”, where observations from a subset from 58 easily studied streams are averaged and extrapolated to apply to large braided rivers that have yet to be adequately studied due to being both discoloured with glacial sediment and being unwadeable.

No wonder we continually get it so wrong.

Thoughtful review of what looks like a great book for anyone interested in our freshwater and marine fisheries. It ought to be used as a reference work for compartmentalised policymakers in Wellington who can overlook the interconnectedness of issues like freshwater, agriculture and fisheries management.

Trout are often scapegoated during discussions of these issues. They’re a touchstone in the argument about valuing the place of native versus introduced species in New Zealand. Some purists might want to return New Zealand’s landscape to before the Europeans arrived, but this is a misguide approach, and sometimes a misdirection from those who want us to ignore the Dairy Industry’s decimation of freshwater ecology.

Besides having an economic value of over a billion dollars, wild trout here are rare and valuable repositories of wild fish genes that have been diminished in North America and Europe through too many hatchery fish. This is so true that biologists come here for their specimens when restocking home waters and to study their gene pools. Wild salmonids populations are also increasingly rare in a world in which climate change threatens coldwater ecosytems.

Even if you could dump enough of the pesticide Rotenone into our rivers and wipe out all brown trout in an attempt to rebuild galaxiid populations, this simply wouldn’t work because anadromous brown trout would simply repopulate below all but the largest natural barriers.

Monetary gains always appears to outweigh the health and balance of fresh and saltwater fisheries.