The rapid extinction of the several moa species from New Zealand has long been debated. Some, in defence of the early Polynesian migrants who had arrived about 1250, have said the flightless bird numbers were already in decline. The Polynesian migrants were conservationists it was claimed.

In 2014 – nine years ago – scientists investigated further and concluded humans were the sole factor in wholesale killing of the birds and in destruction of habitat.

Strangely their findings received little media coverage at the time.

But the reality was that moa were obliterated in a geological “blink of the eye” – just one or two centuries.

The end for the moa was devastatingly fast.

Yet before that, for probably 50 or 60 million years, nine species of large, flightless birds known as moas (Dinornithiformes) thrived in New Zealand. About 600 years ago, moa suddenly became extinct. Their disappearance had coincided with the arrival of the Polynesian migrant humans to New Zealand somewhere in the late 13th century.

Scientists since have long wondered what influence humans played in the decline and extinction.

Others argued the moa was on the way out – naturally – and humans were not responsible.

But the question nagged. Were humans the principal factor? Even the one and only factor?

Then again, or were moas numbers in decline and moa doomed to extinction anyway due to disease and volcanic eruptions?

Scientists went into study mode.

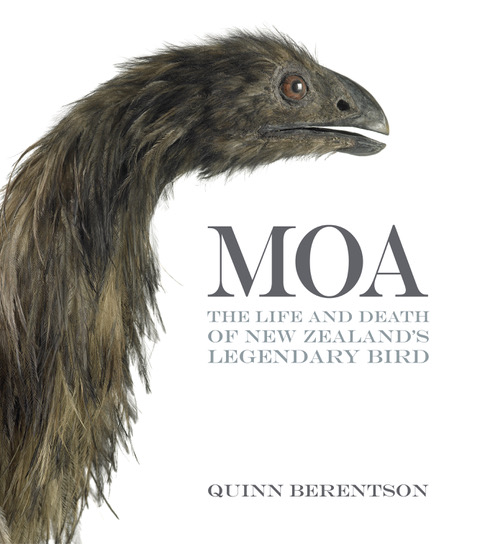

A recent and very impressive book on the moa publishers Potton and Burton (Nelson)

Convincing Case

The conclusions were summed by a Spanish evolutionary biologist. They were emphatic.

“The paper presents a very convincing case of extinction due to humans,” said Carles Lalueza-Fox, an evolutionary biologist at the Institute of Evolutionary Biology in Barcelona, Spain, who was not involved in the research. “It’s not because of a long, natural decline.”

One of the researchers Morten Allentoft, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Copenhagen, outlined the logic behind the research group’s conclusions.

Archaeologists know that the Polynesians who first colonised New Zealand, ate moas of all ages, as well as the birds’ eggs.

“You see heaps and heaps of the birds’ bones in archaeological sites,” Allentoft said. “If you hunt animals at all their life stages, they will never have a chance.”

Using ancient DNA from 281 individual moas from four different species, including Dinornis robustus (at 2 metres, the tallest moa, able to reach foliage 3.6 meters above the ground) and radiocarbon dating, Allentoft and his colleagues set out to determine the moas’ genetic and population history over the last 4000 years. The moa bones were collected from five fossil sites on New Zealand’s South Island, and ranged in age from 12,966 to 602 years old. The researchers analysed mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from the bones and used it to examine the genetic diversity of the four species.

The research team’s analysis found no sign that the moas’ populations had already been collapsing when the Polynesian colonists settled New Zealand. Indeed, the scientists concluded that the opposite was true – bird numbers were stable during the 4,000 years prior to extinction.

Populations of D. robustus even appeared to have been slowly increasing when the Polynesians arrived.

Yet in less than 200 years later, the birds had gone. “There is no trace of their pending extinction in their genes,” Allentoft said. “The moa are there, and then they are gone.”

Humans Alone

Trevor Henry Worthy is an Australia-based paleozoologist from New Zealand, known for his research on moa and other extinct vertebrates.

He commented that the Copenhagen University paper presented an “impressive amount of evidence” that humans alone drove the moa extinct. Trevor Worthy, an evolutionary biologist and moa expert at Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia, was independent i.e. not involved in the research.

“The inescapable conclusion is these birds were not senescent, not in the old age of their lineage and about to exit from the world. Rather they were robust, healthy populations when humans encountered and terminated them.”

At the time he expressed doubts that even the Copenhagen University’s team’s “robust data set” would settle the debate about the role people played in the moas’ extinction, simply because “some have a belief that humans would not have” done such a thing.

Human Tendency

Copenhagen University’s Morten Allentoft, said he was not surprised that the Polynesian settlers killed off the moas. The reality is any other group of humans would have done the same, he suspected.

“We like to think of indigenous people as living in harmony with nature,” he said. “But this is rarely the case. Humans everywhere will take what they need to survive. That’s how it works.”

In late 2014 New Zealand scientist Richard Holdaway, (a specialist in extinction biology), Copenhagen University’s Morten Allentoft and four other scientists completed a study entitled “An extremely low-density human population exterminated New Zealand moa.’

They concluded “New Zealand moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) are the only late Quaternary megafauna whose extinction was clearly caused by humans – – – – – – Polynesians exterminated viable populations of moa by hunting and removal of habitat.”

Very interesting but why should I care about the Moa?

Like most of the species that existed, it’s extinct now.

Species survive and thrive when they are well adapted to the environment they live in.

Environments change and the species that cannot adapt very well become extinct and are replaced by other species that are better adapted.

Our species has not existed fore very long but has been very successful because we can adapt to and even change the environment we live in.

The changes we made to environments were detrimental to the survival of some other species that did not have the “fitness” to survive in the changed environments.

Some species survive at the expense of others.

Some would say that is wrong.

Other’s would say that is natural selection and evolution.

The ability to alter the environment we live in has provided us with many advanages but it could also result in changes that are detrimental to the survival of our species.

Great power comes with greater responsibility for how we use that power.

We need to be careful that we do not end up like the Moas.

When the Polynesian ancestors of Maori arrived in New Zealand after a long voyage, there was an abundance of food. Moa and fur seals were easy to catch. Yet within 200 years, moa and other large birds were extinct. Seals had diminished in numbers.

They introduced kiore (rats) and kuri dogs. Kiore, like any rats bred prolifically and quickly spread throughout the country with devastating effect on lizard, insect and bird populations.

It is somewhat a myth that Maori were great conservationists. They were no different to other humans.

Māori and conservation. In reality, immediate survival would have been first priority.

Before the Polynesians arrived, more than 80% of New Zealand was covered in dense forest. Pollen and charcoal records from over 150 lake, swamp or peat bog sediment core samples give a picture of what happened.

Up to 40% of the forest was burnt within 200 years of Māori settling in New Zealand. I would think fire was used to flush moa out of cover?

Thank you CORANZ for the article of the demise of the moa and to extinction. Really it is tragic. Let’s not hide the truth behind the fabricated idea (lie) that the moa were in decline. It does not matter what ethnicity, humans are invariably destructive in their explouitation if natural resources. Maori were no different.

Excellent exposure blowing away the myth that early Polynesian settlers were great conservationists. It won’t fit the ideology of Willie Jackson, Nanaia Mahuta and other extremists thought or the sycophantical Chris Hipkins, Jacinda Ardern and cabinet disciples.

The pity is the moa were exterminated by the Polynesian migrants. But it happened. There were other herbivorous (vegetarian) birds in the pre-Maori New Zealand fauna. such as the New Zealand pigeon (kereru), kokako , and the red-crowned and yellow-crowned parakeets all which browse a wide range of foliage, which scientists Clout and Hay 1989 pointed out.

Of course there were flightless herbivores with the 11 extinct moa species prominent, the extinct flightless goose and the takahe and kakapo. Scientists Clout and Hay pointed out that kokako and pigeon used to be abundant throughout New Zealand and were at times, significant defoliators of trees and shrubs.

I’ve seen five finger leaves strewn about. People blamed possums. No, it was the native pigeon.

Kakapo were also abundant throughout and fed widely from ground level up into the canopy say scientists. Not generally recognised is the very considerable populations of insects are browsers in unmodified New Zealand forests and shrublands.

Moa were undoubtedly the dominant browsers from ground level to a height of about 3 metres.

There are huge amounts of information on moa in Quinn Berentsons award winning book “Moa” . It fails me that the many so called experts can’t understand what he has written, all the respondents to this post seem to understand what part the moa played in our forests, mountains and lowlands and what part their replacements have made not exactly the way moa did but close to it, certainly better than it would have been without them.

Second attempt to post:

Of course the early immigrants killed off the Moa just as the early immigrants to North America did for the Passenger Pigeon (now extinct) and almost did for the bison which, thankfully survived, just, and now once again prospers due to careful and enlightened management by humans.