by Tony Orman

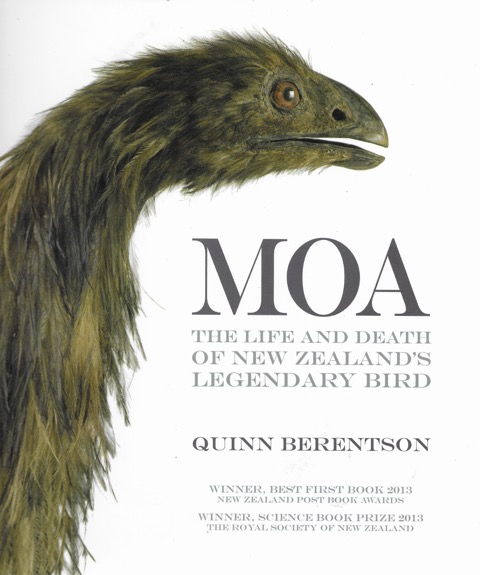

Quinn Berentson’s book “Moa – The Life and Death of New Zealand’s Legendary Bird” published in 2012 has been reprinted.

It is a very welcome reprint for the story of the moa is a fascinating one that deserves to be retold for new generations.

Quinn Berentson of Dunedin, scientist, writer, documentary film maker and photographer, is well qualified to tackle the task of researching and writing about a remarkable bird. Once he began to dig deeper into the wealth of written material and speculation, he realised there was much more to the story than might be first imagined.

“It covers not just the strange attributes of the flightless giants—but also the unlikely series of events and people that were involved in turning the moa from a monster of ancient legend to an international sensation in the late nineteenth century.”

Quinn is referring to the role of the moa in debate within the wider scientific fraternity of the 19th century and the intrusion of human egos..

Incredibly human nature took over and highly personal and nasty infighting soon broke out amongst those who competed to study them. Britisher Richard Owen, a scientist of an enormous conceit and competitiveness, with a spiteful, vindictive streak, possessively clung to his “Father of the Moa” reputation that was founded on his publishing of a moa paper in 1838. Quinn describes him as the “most unscrupulous scientist in Britain” who would without conscience hijack others’ discoveries. Owen clashed viciously with another scientist Gideon Mantell and later Mantell’s son, Walter.

Meanwhile in New Zealand noted early explorers like William Colenso and Bishop William Williams innocently entered the fray. In later years geologists the ambitious and ego-driven Julius von Haast and James Hector became embroiled in feuding of the moa.

Quinn Berentson skillfully brings the human jostlings and clashes over the moa to light.

Blink of Eye

But human conflicts aside, what of the moa?

It seems incredible also that the moa was wiped out in such short time. “seemingly in the blink of an eye” – geologically speaking – says the author. During studies on the Otago goldfields Quinn found many references from European gold mining days to numerous moa bones.

“I became increasingly fascinated and it evolved into a story begging to be researched and told. Like I did, most New Zealanders know stuff-all about the moa.”

With little competition and no ground predators moas thrived for some 60 millions years.

“They adapted and diversified to fill virtually every terrerstrial environment, from sand dunes to flax swamps, deep primeval rain forest to frozen sub-alpine tussock. Some were the size of turkey while the largest, the giant moa became the tallest bird to have ever lived on the planet.”

Then the Maori arrived from Polynesia. Seemingly in a geological blink of an eye, the moa disappeared, erased from history so quickly and thoroughly that today New Zealanders scarcely give them a thought.

“They have become creatures of myth and urban legend – ghosts in the bush,” says Quinn.

How Many?

Moas were flightless birds up to 3.5 metres high with the giant species having succulent 30 to 40 kg drumsticks a metre long. The birds were relatively easy to kill while human-induced bush fires ravaged their habitat as well as killing many.

Quinn Berentson estimates the moa population was at least one million. But scientist Les Batchelar in 1986 put the number at between six and 12 million. The late Dr Graeme Caughley with six million reckoned more in line with Batchelar. But who can say for sure? Really no one.

“It is difficult to estimate the total population of either moa or moa hunter involved in the great slaughter but it is obvious that a relatively small population of humans wiped out an enormous number of moa,” says Quinn.

DNA testing just last year revealed there were very likely nine species. Moas lived everywhere in New Zealand except the Chatham Islands. The giant three metre plus moa lived in both the North and South Islands. The metre high Upland Moa in the South Island high country and the medium sized Crested Moa in north-west Nelson. Then there was the Heavy-footed Moa and Eastern Moa in the eastern South Island, the turkey-sized Mantell’s Moa in only the North Island, the squat Stout-legged Moa in all the North Island and eastern South Island and the smallest of all but most widespread – the Little Bush Moa – all of the North Island plus western and southern South Island.

Moa Meat-works

The slaughter of the moa was amazingly rapid. Science has revealed within just 100 years of human settlement, moa were extinct in most areas of New Zealand. Radio-carbon dating from moa bone and charcoal suggest the most intense moa hunting happened across the 14th and 15th centuries.

“The huge moa meat-works along the east coast of the South Island were at their peak at the same time as the Ming Dynasty of China, the Inca Empire in South America and Christopher Columbus’s discovery of the New World in 1492,” says Quinn..

The life and biology of moa times is fascinating in itself. The moa’s only natural predator – before the invasion of Polynesians – was the Haast’s Eagle which was at the top of the food chain in ancient New Zealand.

The giant eagle had a three metre wingspan and Quinn estimates that by about 1350 as the Haast’s eagle’s habitat in eastern South Island had been burned and the moas exterminated, they died out. It is probable the eagles were also hunted by humans.

The blitzkrieg was swift. For example, it seems within 10 years the Coromandel moa population was exterminated.

The 300 page book is a long yet utterly absorbing read thanks to Quinn Berentson’s meticulous research and skilful narrative, enhanced by numerous illustrations, both photos.

And a word of praise for publishers Potton and Burton for a typically excellent production.